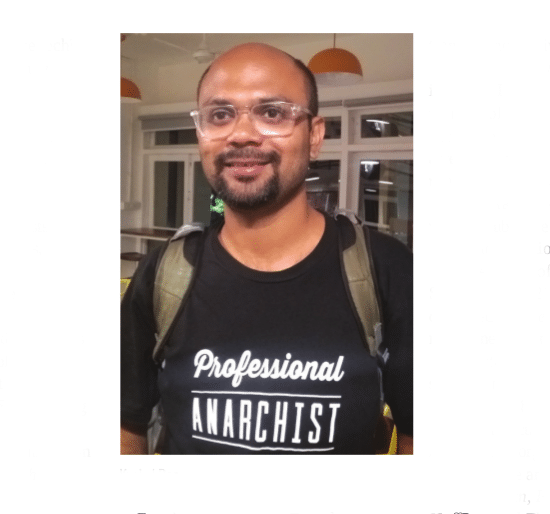

Kushal Das is bright, Indian and articulate. He is one of the small but growing number of desi techies involved with global FOSS projects. But he plays an unusual role today, and speaks a language that focuses on press freedom, whistleblowers, and allowing journalists to work effectively. His current area of focus is SecureDrop, which he describes as “a widely used secure digital platform for sources to anonymously submit materials to journalists.”

From being a hard-core techie, Kushal Das has taken on new roles – looking deep into how technology can help society, in very direct ways. And to do this, he focuses on the seemingly abstract (but very real) issue of press freedom. His weapon: SecureDrop.

SecureDrop allows journalists to hear from all possible sources, and from whistleblowers. Both can communicate securely with each other, using this tool.

Kushal Das was one of the founders of the Linux Users’ Group of Durgapur, the third largest city in West Bengal, after Kolkata and Asansol. Some among us might recall this LUG as an active group. Its online tracks and archives can now be found at dgplug.org/archive/.

Das says that the year 2005 marked his first FOSS.in conference, which was organised by the late Atul Chitnis and team, at Bengaluru. He adds, “I worked all my life on free software projects, nine years of that officially at Red Hat, and the last three years as a Fedora Cloud Engineer. I’m a core developer of Python, and have also been part of many different projects. At one time, I had commit permissions in KDE, and now am also part of the core member team of the Tor Project.”

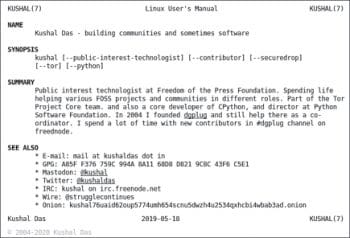

Kushal Das describes himself in a brief online ‘Linux User’s Manual’ thus: “Public interest technologist at Freedom of the Press Foundation. Spends life helping various FOSS projects and communities in different roles. Part of the Tor Project Core team, a core developer of CPython, and director at Python Software Foundation. In 2004, I founded dgplug and still help there as a co-ordinator. I spend a lot of time with new contributors in #dgplug channel on freednode.”

More recently, Das has been spending time working on and raising awareness about SecureDrop.

SecureDrop was earlier called DeadDrop. It was co-created by noted transparency activist Aaron Swartz (1986-2013). Swartz’s life is a story in itself. To put it briefly, the young techie, political organiser and hactivist committed suicide after the police arrested him in a controversial, high-profile case. (For more details, see ‘The Story of Aaron Swartz’ documentary via YouTube; the link is given in the References section.)

Later, this software was called Strongbox. In 2013, it was first deployed by The New Yorker, the weekly magazine known for its journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons and poetry. The Freedom of the Press Foundation took it up, and SecureDrop is now used by many major organisations worldwide. Among these are The Washington Post, The Guardian, ProPublica, Gawker, HuffPost and The Intercept, apart from The New Yorker. A study shows that SecureDrop has actually led to many stories being published.

When I briefly met Kushal Das at Goa, he said, “We defend and protect public interest journalists and media organisations. We build tools and technologies to work together.”

Das says that the two important aspects of the SecureDrop work cater to journalists and whistleblowers. A whistleblower is someone who exposes any information or activity that is illegal, unethical or incorrect, from within an organisation. The organisation could be either a private or public (government) one. On the other hand, a journalist is a person who collects, writes and distributes news, either through the means of formal or informal journalism, even blogging.

Sometimes, these two need to communicate safely and in privacy. When the identity of the whistleblower gets leaked, it can become risky for him or her. Think of an Edward Snowden or a Chelsea Manning. Hence, the communication needs to be done in a very secure environment.

That’s where SecureDrop comes in. “The [FOSS] program helps a whistleblower to release information to a journalist. If you get caught releasing information, you could be thrown into jail. Or, you could get killed. Whistleblowers take a lot of risks. They realise that something pretty bad is going on, and then they step up to release the information,” says Kushal Das. Incidentally, some lists show India among the top ten most dangerous countries for journalists, globally.

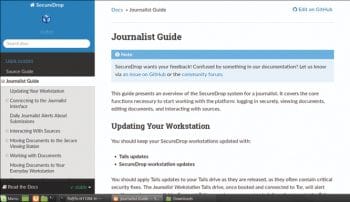

SecureDrop is actually a Web application. It can be deployed by big media organisations, small media outfits or even by an individual journalist — on their own server, inside their own office.

“We provide certain suggestions on what kinds of servers could be used — right now we suggest two Mac minis. If you open The Washington Post, The New York Times or The Intercept online, you can open SecureDrop on the site, using a Tor browser,” Das says. Tor incidentally is FOSS software that is used to enable anonymous and secure Internet access.

If you’re a first time user, you can visit a news website you trust and submit a document. Later, you might plan to return to the site, to check if a response has been given to your submission.

Das adds, “We do not have a password based system; instead there is a passphrase. If you’re coming in only once, to submit documents and go away, you don’t have to remember this. If you’re returning, we suggest you write down the passphrase, memorise it, and then destroy the paper. We provide a guide on how to leak: don’t do it from your office network. Preferably buy a second-hand computer, or go to a public cafe where others are browsing, and make sure your screen is not visible from anywhere else. And then don’t return there.” So there’s a lot of work involved for the whistleblower. But safety comes at a price.

At a single go, the software allows you to submit up to 500MB of data. It is localised, and can run on many different languages.

“It doesn’t have any JavaScript, which is one of the big evils, in every possible way. JavaScript can do many fancy things, but it can also blow away all your privacy and security,” adds Das.

Journalists have a different app running, in the same server. You have to log in with your passphrase and your OTP (one time password). Every source will get randomised names. Even the randomised ‘source’s’ name will not be revealed to the journalist.

Sources need to know which journalists to send their drops to, and how. Even the computer you use can be critical. If you plan to blow the whistle on a big scam involving powerful organisations, you need to take some precautions. Walk into a store with cash, buy the hardware, and get out. There will be instructions on how to open up the hardware, and avoid any unauthorised access to the box.

SecureDrop can be accessed from a special room within the news organisation’s premises, and journalists use dedicated laptops in these rooms. The advice is to never carry any other electronic device with you when you go to access your journalist workstation. Also, you’re not supposed to take the laptop out of the secured locked room. After downloading a file onto one computer, save it on a USB drive or a write-only CD/DVD drive. Then place it onto a second computer, which can decrypt and show the original messages or files from the source.

Nowadays, even looking at the dots and full stops of a PDF document can tell investigators who leaked it, Das warns.

Das believes that all engineering students should learn about ethics. “It took me time to realise why ethics is so important for us,” he says.

He also feels that the issue of using and misusing the Net is sometimes misunderstood or exaggerated, in particular with regard to the Tor Project. Das points to some newspapers that have continually written about the ‘dark net’, creating all kinds of paranoia about it. When asked to write about the other side of the story, informing the public that Tor helps people with security and privacy, the press folk simply say, “That doesn’t sell,” Das complains.

So that’s a lot of work to be able to ensure the truth gets told. But history tells us, it’s worth it.