Gone are the days when open source was a concept that applied mainly to the arts and software. Today, open source fires innovation in many things, from gadgets and cars to prosthetic limbs and advanced military vehicles. Every month, in this section, we take a peek at the open source aspects of some interesting devices, applications, tools, etc.

Truly the car of the future

Visteon Corporation has developed the e-Bee, a concept car based on the Nissan Leaf. It has all the automotive electronics you would like to see in your future car and if Visteon’s estimate is right, your dream might come true by 2020. The e-Bee has everything from entertainment and mobility solutions to safety and comfort. It is filled with loads of technology, including a personalised human-machine interface (HMI), touch-screen instrument panels that give information on vehicle controls and social media connections, a head-down projected main display in front of the driver, a rear view with 360-degree visibility and augmented reality features, tech-agnostic wireless charging, near-field communications (NFC) for a personal link between user and vehicle, climate control system, cloud connectivity and car-to-car communications to improve driver information about collisions, hazardous roads, curve speed warnings and traffic flow, and much more.

The open twist: e-Bee’s extremely advanced audio, video and information platform is based on open technology, and is designed to be upgraded automatically throughout the car’s lifetime. Using open architecture and open source software that meet GENIVI standards, this solution can operate as both the HMI and Media-Oriented Systems Transport (MOST) master and provide up to four independent instances of HMI. The system integrates a wide range of functions into a single scalable module while providing varied connectivity features from Bluetooth and Wi-Fi to Internet connectivity, remote HMI configuration, and software and feature updates. The open software solution leverages features developed by several open source software GENIVI members, maximising re-use and robustness, while reducing the engineering costs to develop such complex systems.

Micro-clouds for a connected classroom

One of the best devices demonstrated at CES 2013 was Marvell’s SMILE Plug, which is an easy-to-use, low-power cloud computer that claims to turn a normal classroom into a connected, secure and highly-interactive learning environment by setting up a micro-cloud for up to 60 students. It facilitates what Marvell calls Classroom 3.0, by enabling the delivery of educational content and applications via a range of mobile devices including smart phones and tablets. The device is powered by Marvell’s high-performance, low-power ARMADA 300 series system-on-a-chip (SoC) and the company’s industry leading Avastar 88W8764 wireless chip. Network connectivity is through Gigabit Ethernet, and peripheral devices can be connected using USB 2.0 or Wi-Fi.

The open twist: The SMILE Plug runs on a completely open source platform, which makes it easy to develop or port any additional learning applications. It is based on Arch Linux for ARM, NODE.js, and Stanford’s Mobile Inquiry-Based Learning Environment (SMILE) and software development kit (SDK). Other open components include the Node Package Manager, the Plugmin administration API and UI (that runs on Android-based client devices) and the SMILE Junction Server Administration Client.

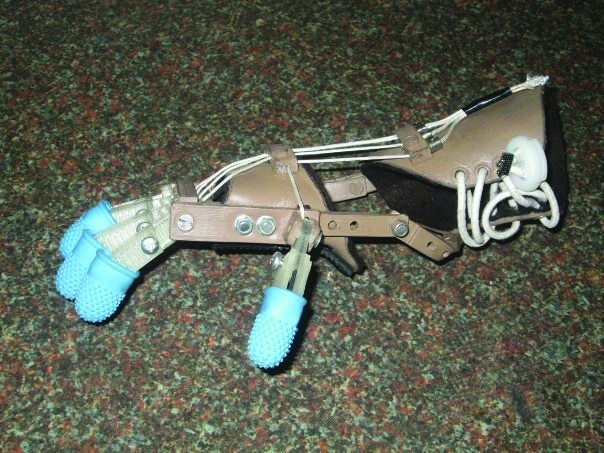

An open source prosthetic hand

When Richard Van As of South Africa lost four of his fingers in a sawing accident, he stumbled upon the designs of a prosthetic hand on YouTube. Together, Van As and the original developer Ivan Owen from Washington perfected the designs to suit Van As. Soon, they decided to make this a worldwide campaign to help those who needed prosthetic hands, and uploaded the designs of their body-powered device in the public domain. They continue to work on the designs, and welcome donations, suggestions and improvements. They also received two 3D printers as a donation from Makerbot, which allows them to synthesise their designs. In January, they used these designs to develop a 3D-printed prosthetic hand, which they called Robohand, for a South African five-year old boy called Liam, who was born without fingers on his right hand. The Robohand suits Liam quite well, and he is now able to play, take care of his personal needs and attend school-where he shows off his mechanical fingers!

The open twist: Robohand is a typical example of low-tech mechanics, fast-prototyping and the power of open source. It is made of 16 3D-printed pieces and 28 common, off-the-shelf items like nylon cord, nuts, bolts and rubber thimbles. The prosthetic hand is controlled by a system that reacts to the movements of the arm. Apparently, Van As and Owen do not seek any profits from their design they just want to get enough funds to create prosthetic fingers for whoever needs them, which is why they decided to publish the information in the public domain. The original designs are available at http://chaincrafts.blogspot.in/2012/08/finger-prosthesis-design-details.html, and Liam’s hand design is available at http://www.thingiverse.com/thing:44150. The designs will soon be made available in more detailed formats. By publishing these designs in a public forum, they now fall under the concept of prior art (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prior_art). This means that the developers have given away their right to patent the design, while also ensuring that others cannot patent it, thus keeping it free and public.

New powder-based 3D printing technology

Alex Budding, a researcher at the University of Twente, Singapore, has developed a new rapid-prototyping technology called Pwdr, a powder-based technology that can be extended to enable multi-colour 3D printing. Pwdr is made entirely with off-the-shelf components. The chassis, tool head and electronics can be purchased for less than 1000 and assembled within a few hours using Budding’s designs. Instead of using layers of melted plastic, Pwdr uses an HP inkjet cartridge. It deposits a liquid binder, mixed with ink, onto a layer of white gypsum power. Then a roller drags a thin layer of powder across the surface. The process is repeated till the whole object is formed, layer over layer. Then, the object has to be removed from the printer, dusted off and dipped in clear glue that helps solidify it.

The open twist: Pwdr has a maximum build size of 125mm x 125mm x 125mm, a minimum vertical step size of 50 microns, and speed of around 1 minute per layer. It has a pretty decent print resolution of 96 DPI. While there are quite a few open source printer designs already available on the Web, none are powder-based. Budding felt that powder-based printers have a specific application in the field of ceramic materials. His design and code have been open-sourced, and are available on his Github page (http://pwdr.github.com/). While the current design only prints in one colour, the technology could be used to develop a full-colour powder-based printer, thanks to the open design. You could also try to replace the inkjet with a laser, turning the system into a selective laser sintering (SLS) tool. There is also scope to improve the inkjet head, find some way to dispose of the excess powder, or enhance the user-interface. In one of his articles, however, writer Joseph Flaherty issues a word of warning to entrepreneurial readers: Budding claims that the core patents on this technology expired in 2010, but 3D Systems, ZCorp’s parent company, has recently flexed its legal muscles to defend other disputed patents, so perhaps you should consult a patent attorney before putting a model on Kickstarter.

Design a tank with open source META toolkit

The USA’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has developed open source software called META that enables anyone to become a tank engineer. The tool will be released shortly, and apparently the framework can achieve the design, manufacture, integration and verification of complex ground vehicles 5X faster than the conventional design-build-test approach. DARPA has also launched a series of contests, the FANG Design Challenges, which encourage engineers to use the toolset to develop vehicles such as an amphibious tank. The details are available on http://www.vehicleforge.org/. The VehicleFORGE website will allow social collaboration around open source vehicle design to compete in the FANG Design Challenges.

The open twist: META is completely open source. It is not based on any one particular approach, metric, technique or tool. The goal of META is to develop model-based design methods for cyber-physical systems that are extremely complex and heterogeneous. It features a structured design flow employing hierarchical abstraction and model-based composition of electromechanical and software components. It further optimises system design, and uses probabilistic formal methods for the system verification, thereby dramatically reducing the need for expensive real-world testing and design iteration. DARPA also aims to develop a component and manufacturing model library for a given airborne or ground vehicle systems domain through extensive characterisation of its features, interactions and properties, right down to the numbered part level. The library will also include context models to reflect various operational environments, and develop a verification flow that generates probabilistic certificates of correctness for the particular cyber-physical system based on stochastic formal methods.