The electronics industry is the pioneer when it comes to ingredient branding. There have been many great and iconic cases of this practice, and there is a lot to learn from them. This article analyses two such cases in the first part of this two-part series.

The computer industry really brought ingredient branding to the forefront. Assembling desktop computers using branded components was a viable way to save money for the end user. An assembler could take a Seagate hard disk, Intel processor, Samsung monitor, Logitech mouse and, like magic, you had a computer as good as an HP or Compaq desktop.

The slow shift to the laptop is what eliminated the ability to ‘assemble’. However, by then, the industry was operating with well-known ingredient brands for the processor, hard disk, monitor and mouse. Although the assembling industry was not threatening the computer brands, the result of this ingredient branding was that there was not much difference between an HP, a Compaq or an IBM product.

What is an ingredient brand?

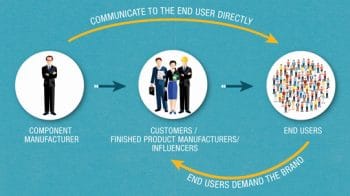

When a component maker builds a brand, it is called an ‘ingredient brand’. An ingredient brand is not built with the component maker’s customer as the target audience; rather, it is built with the end user in mind. When the end user knows you well, it creates a ‘pull’ for your brand.

Many component makers feel that if their customers know them, and these customers are also well-known in the industry for providing quality products, they have built a brand. But I beg to differ. The end user, too, needs to know them and their products. And these component makers need to have created some ‘pull’ for their products in order to truly call themselves brands.

Commoditised category

Till the first company in the component category takes the step to build a brand, the category remains largely commoditised. And the players remain largely unknown to the end user. Because of that, no one player can command a price premium in every sale it makes. Players often build relationships with their customers by providing good quality at the best possible price and look at increasing sales based on that, rather than on the strength of their brand.

Benefits of ingredient branding

- For the finished product/OEM: Finished products comprise components. Let’s assume one of those components is branded. The maker of the finished product leverages the ingredient brand to sell. It hopes to give the impression that ‘this is a high quality finished product, because the ingredients used are also of high quality’. This adds credibility to the finished product and allows the makers to charge a premium.

- For the ingredient brand: The single biggest advantage of investing in brand building is the ability to charge a premium. Once the ingredient brand has built a name for itself, the end user desires finished products that contain this brand. This allows the ingredient or component maker to charge a premium, which the finished product maker passes on to the end user.

Another critical benefit for the ingredient brand is ‘not being substituted’. Once the finished product starts relying on the ingredient’s brand equity to make a sale, it also reduces the ability of the finished product maker to substitute the ingredient with another component. Some might argue that this is even more important than charging a premium, because it ensures business continuity.

Be the first mover

But one critical factor for a component to become an ingredient brand is that it needs to be the first mover. The first player tends to become the market leader and remains so, provided of course, the company doesn’t make a hash of its marketing efforts.

The first mover usually is seen as the expert by the end user. Players that follow—and yes, they will follow—will be seen as making ‘me-too’ products. Of course, there have been exceptions to this rule. And there are ways to get a slice of the pie even when you are not first, but that is for another day.

What I have spoken about till now are the advantages of ingredient branding. How to go about doing this is equally important, and the best way to learn is by looking at specific cases of companies that have done this kind of branding well.

The way Intel did it

This is the case of the century with regard to ingredient branding. It is one of the most successful cases ever.

Let’s go back to before Intel was known to the world. By 1990, Intel had already launched its 386 chip, which was being supplied to PC manufacturers like Compaq, IBM and HP. But things started to turn south. Intel started losing market share to Cyrix, another chip maker. The latter was reverse engineering Intel’s chip and selling it for half the price. PC manufacturers were willing to replace Intel chips with Cyrix chips. After all, who would not if they were getting similar quality for a lower price.

But Intel was ambitious. The product it was fighting was a ‘me-too’ and Intel did not want to battle it out based on price. What it did next changed the computer industry forever. And this is why I referred to it as the ‘case of the century’.

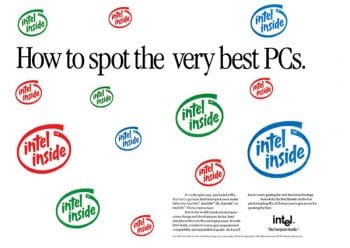

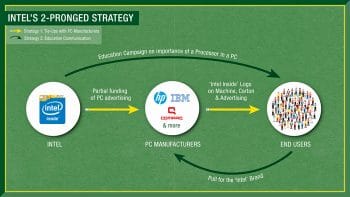

Intel did two key things. The first was a business model decision. The company chose to work with its customers differently. It decided to partner with them. And this was not just in name, like many customer-centric programmes are. It was not just smoke and mirrors. Intel actually put its money where its mouth was. It took a big risk by deciding to part-fund its customers’ marketing efforts. In exchange, its customers put the ‘Intel Inside’ logo on the machine and carton as well as in their advertising. This was a mutually beneficial relationship to build the PC market.

Intel’s second step was an education campaign aimed at the end user. The company realised that end users knew nothing about what was inside the box, and probably found things too technical to make an effort. So Intel decided to educate the end user on the importance of the processor. The campaign it developed had two objectives—the first was to position the processor as the heart of the PC (as what is responsible for the speed of the PC), and the second was to make end users aware of the compatibility of the processor with all kinds of software.

Both these efforts helped build a brand for Intel with the end user, thereby creating a ‘pull’ for the brand.

Takeaway: Intel had made the end user its target audience, even though the end user was not buying a processor but buying a computer. This education campaign usurped the importance of the computer. By calling itself the heart of the PC and saying it was responsible for its speed, Intel made itself the most critical component of the PC—and over time, more important than the brand of the PC. It made sure that it did not sign any exclusivity agreement with any one PC manufacturer. That move ended up reducing the differentiation between PCs. IBMs, HPs and Compaqs all had Intel processors. Because of that, the focus moved from the PCs to the processor.

Many companies partner and develop products tailor-made to the requirement of their customers. But Intel went one step further than this and that made it the market leader. Everyone started depending upon its processors, and the rewards were amazing. The brand soon began charging a 400 per cent premium over Cyrix and got back the market share it had lost.

And it has dominated the PC market ever since.

This is what Dolby did

When we think of Dolby, we think of incredible sound—in our films, in our TVs and in our mobile phones. Dolby is everywhere. But there is a lot to learn about how a company can get to this point—the things it did right and the things it did wrong.

Ray Dolby, who died in 2013, was an engineer who dabbled in sound technology even before he founded the company. The initial technology he came up with was a ‘first in the world’ type. He had figured out how to reduce the hiss that happens when recording sound. He called that ‘Noise Reduction (NR)’.

That was the beginning of an incredible journey. He first got sound studios in England to adopt NR. The American sound studios soon followed. He rode the whole wave of cassette tapes and players, and moved into providing NR sound for movie theatres.

At the very beginning, Dolby had decided it would manufacture professional products only and license the technologies appropriate for consumers.

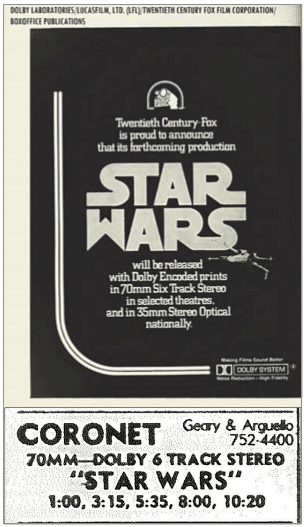

But the big inflection point came when Star Wars used Dolby to provide sound for the film. Even though state-of-art sound was being used in albums and concerts—in movies, it was a commoditised category. Stephen Katz, the sound consultant from Dolby who worked on Star Wars, said, “The sound was a very important component for Star Wars, and it was a component that Hollywood virtually ignored. People used to tell me, ‘Nobody listens to the sound’.” Well, not until George Lucas decided to change things. It is his vision that Dolby brought to life.

None of the movie theatres were fitted with Dolby sound, but Twentieth Century Fox insisted that if they wanted the 70mm print (vs the 35mm), they needed to install Dolby. And because very few movie theatres had made that shift, Star Wars was initially released with only 40 prints as against the usual 800 prints. And only three prints had Dolby sound. But the film created so much magic that things took off from there for Dolby. Movie theatres were clamouring to have Dolby sound. Without Star Wars, Dolby would not have got where it did. But equally, without Dolby, Star Wars would not have been as magical as it was. The sound added a lot to the film. So much so that the industry henceforth looked at sound differently—it was no longer a commoditised product.

Dolby’s journey did include a speed breaker. The company did not anticipate the impact digital audio would have on cinemas. Sound, till then, although of excellent quality, was analogue. Then an entrepreneur called Terry Beard, along with Steven Spielberg, Universal Studios and other investors, created Digital Theatre Systems (DTS). Dolby lost out and took a few years to gain back its leadership in the industry.

Dolby’s business focus has been innovation and patent protection. It has made most of its money through licensing. As of 2018, 90 per cent of its revenues come through licensing and 10 per cent through products and services.

Now, Dolby has entered every aspect of our lives. The movie theatre product is Dolby Atmos. This has moved beyond audio, into video, with the addition of Dolby Vision. Its home theatre product is Dolby Digital Plus. Dolby works with companies to provide its products on smartphones, TVs, tablets, games, DTH companies, streaming services, headphones, movie theatres, sound studios and many more.

Takeaway: Dolby is a company that has innovated consistently to better its own products. This focus on innovation has meant that it has rarely needed to rely on buying technology from outside the company. Its decision to focus on top-end professionals and leave the rest to licensing ensured a continuous inflow of funds, so much so that the firm did not feel the need to go public until 2005. Its relentless focus on patenting has resulted in it having 8100 issued patents and 4200 pending in 100 countries, as of 2017.

Dolby also works with its customers to ensure there are no design mistakes in its products and that these are of high quality. One of the key decisions that Dolby has taken is to keep licensing affordable so companies would rather use the technology than not. This has made the technology accessible and available everywhere, and largely kept competition out. This approach has prevented Dolby from being substituted by DTS. Even though it did lose out to DTS for a while, it has made a comeback.

The bottom line

Before Intel and Dolby decided to build ingredient brands, the products of both companies belonged to commoditised categories. It always takes a bold decision on someone’s part to make the moves that these companies did. Both Dolby and Intel have built brands which target the end user of the finished products that their products go into, so that there is a ‘pull’ for their brand.

Intel provided funds to its customers’ marketing budgets, which built loyalty and prevented substitution. And in Dolby’s case, the licensing was affordable and the technology was great. That is what prevented others from dominating and enabled Dolby to make a comeback when DTS had taken the lead with digital audio.

The principles followed by these firms can be used by many businesses:

- To create partnerships with your customers.

- To focus on the products, innovating all the time to make them redundant, so that no one else does that to your products.

- To recognise the stage your product is at, and to know whether consumer education or competitive communication is required.

- To keep a look out for new technologies and to not miss them like Dolby did with digital audio.

- To use the big moments in your industry to your advantage, as these can become big inflection points, the way Dolby did with Star Wars.