Open source has not just helped some established organisations to grow further but also empowered many startups to compete against big enterprises. iText is one such example. The Belgium-based company brought out the world’s most used and actively developed PDF library by deploying open source technologies. Jagmeet Singh of OSFY talked to iText founder Bruno Lowagie to get some insights about his venture and his views on the growth of open source. Edited excerpts from the interview:

Q How did you get the idea to launch iText?

I got my first computer at the age of 12. That was 34 years ago (in 1982) and things were very different back then. Today, people get a computer and they can start working right away. In those days, there wasn’t that much software around and what was available was very expensive. At the age of 14, I had already written my own database system and my own text editor. I didn’t know about the Internet back then; I was the only kid who owned a computer in my town.

At the age of 18, I went to college, but I didn’t study computer science or software engineering. I picked civil architectural engineering. I learned how to design buildings, not software. I returned to software development only after I graduated. I changed jobs four times in the first three years of my career — working for different software integrators first, then finally for Ghent University. During my spare time, I continued working on personal projects, but none of them were successful until I released iText.

My job at Ghent University consisted of rewriting the software for the student administration. Previously, professors had to enter the grades of the students on a diskette using a Clipper application that only worked on DOS and that could be used to print lists on an HP printer (and only on an HP printer). These diskettes were then passed on to an administrator who extracted the data and uploaded it to a central database. I promised Ghent University that I would offer them an intranet application that could be used on any computer using nothing but a browser. I also promised that I would provide lists in the PDF format so that they wouldn’t depend on one particular brand of printers.

The year was 1998. I used Java servlets to create the intranet application. Java has existed since 1995 and the first PDF specification was released in 1993. I was convinced that I would be able to find PDF software that could be used to create PDF files on-the-fly in a server application. I was wrong; in those days, PDF documents were created on the desktop by human beings who had access to a GUI. I didn’t find any Java PDF software that met the requirements of my project — I needed to create PDFs on the server, without a GUI and without human intervention. Moreover, the software had to be fast; when people asked for a list with 20,000 student records, they expected that list to be available in fractions of a second. Nobody wants to wait for minutes to get a document from the Internet.

So I started reading the PDF specification during the Christmas holidays of 1998 and I began to hate PDF. Reading the PDF specification to understand PDF is like reading a dictionary in the hope you’ll learn a language. I succeeded in writing the first PDF library in six weeks’ time. It served its purpose, but a developer really needed to understand PDF inside-out if he or she wanted to use that first library. That wasn’t trivial; I was the only person on my project team who understood the code. As a result, I was the only person who could debug and maintain that part of the project. That’s not a healthy situation.

After having worked with that library for about a year, I suddenly saw the light — I started to understand and love PDF. I realised that my first library was all wrong and I wanted to rewrite it from scratch. My employer didn’t understand why I wanted to do that — why fix something that isn’t broken? But I persisted and I started writing a new library in my spare time. I called this new library iText, and I released the first version as open source software in February 2000.

Q What distinguishes iText as an open source library in the market?

The strength of iText is its ease of use. Thanks to iText, developers could start creating PDFs without having to know anything about PDF as a file format. My first PDF library required that you knew how to write PDF syntax. With iText, I created an abstract layer that allowed developers to work with concepts they knew: paragraphs, anchors, lists, images, tables, cells, etc.

iText was also built for speed. As I needed to serve PDFs to a browser, I had to break some design patterns and create an architecture that was somewhat out of the ordinary, but I succeeded in making iText really fast. Over the years, several other PDF libraries emerged, but iText is still the fastest in the market.

To keep ahead of the other vendors and the copycats, we continued our investment in further development. Back in 1998, I read and followed the PDF specification. Today, iText is a member of the ISO committees for PDF and we help in writing the specification, along with companies such as Adobe, Callas, Canon, Datalogics, and many other vendors. We can make this investment because we have an open source business model that works. I don’t know of any other open source PDF library that can keep up with the newest standards in the field of PDF.

Q You recently gave a lecture on intellectual property (IP). Do you think knowledge about IP is crucial for developers in the open source avenue?

When you write software — whether it’s open or closed source software — you create intellectual property. So my answer is yes; knowledge about IP is crucial for developers in the open source as well as the closed source avenues. A developer can’t afford to be ignorant about intellectual property. I notice that many developers assume that source code they find on the Internet can be used as if it were completely free and as if they can use it without any problem. That’s a misconception.

If you find a piece of source code without a licence note, the copyright of that code is proprietary to the developer who wrote it. You can’t use that source code without the explicit permission of its author. To solve this problem, we use licences. Commercial software vendors work with an End-User Licence Agreement. Open source developers add a free or open source software licence to their code. There are many different flavours of open source licences, ranging from the very liberal MIT or BSD licences to the stricter AGPL licence.

If you’re an open source developer, you have to choose your open source licence wisely. For some projects, using an Apache licence is the best choice. For other projects, it’s best to choose a GPL-style licence. For iText, I started with the LGPL. After a while, I added the MPL, because people from the industry had a problem with the LGPL. In 2009, I switched to the AGPL and although some people will disagree, the AGPL is still the best licence for a project like iText.

If you’re not an open source developer, but you want to use open source software, you have to know the implications of the licence that was chosen for that particular open source project. There may be specific restrictions you have to take into account if you want to use that software for free.

Q iText is already one of the successful open source enterprises. What are the factors that help monetise an open source project?

I have tried many different business models to monetise iText, starting from donations, advertisements and documentation to selling support and professional services. It took me from 2000 to 2009 to discover that none of those models worked for me. But during this decade and thanks to all these experiments, iText had become ubiquitous — every Java and C# developer knew that iText was the library you needed to use if you had a PDF-related requirement. No developer was aware that I almost gave up on iText in 2008 because I could no longer maintain the project. My son was in hospital with cancer. I had just started my first company for iText and that company wasn’t making any revenue. If I didn’t find a sound business model soon, iText development was going to die a slow and painful death, in spite of its success, or maybe even because of its success. Fortunately, I found the right business model just in time.

In 2009, we changed the licence from LGPL/MPL to AGPL, making it mandatory for many companies to purchase a commercial licence if they wanted to continue using iText. In 2009, iText made its first substantial revenue and we have been growing ever since.

The most essential factor for an open source software project (any open source project) is whether people are willing to give something back for their use of the software. I find it hard to understand that some developers think that they enrich themselves by using other people’s work without ever giving something back. Compare it with a parasite; a parasite lives on a host and benefits by deriving nutrients at the host’s expense, sometimes killing the host in the process. To make an open source project successful, you need to create a mutual symbiotic relationship between the provider and the user. This can be a business relationship where the user becomes a customer, but that’s not the only option. Whatever works best depends on the nature of the project.

Q Why do startups and SMEs need to focus on open source deployments instead of some closed source solutions?

I recently read the article ‘Programming By Poking: Why MIT Stopped Teaching SICP (The Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs)’. It’s the course that taught many software engineers how to write good code. The course has now been abandoned because engineers have changed. Today, developers use libraries without fully understanding what happens under the hood of the library. To quote Professor Sussman: “You grab this library and you poke at it. You write programs that poke it and see what it does. And you say: ‘Can I tweak it to do the thing I want?’”

I see this happening every day when I’m on StackOverflow. It’s as if developers nowadays only know one book, titled: ‘Copying and Pasting from StackOverflow.’ I answer questions from people who say, “We don’t care about how iText works, we need iText to do this!” I often wonder why developers who say such things aren’t ashamed. Where is their honour?

I can understand why people use libraries. I use libraries myself because the world has gotten so complex that you can no longer master every discipline yourself and it would be stupid to reinvent the wheel. It’s only normal that you try to reuse work that has been done before.

Nevertheless, you should have some knowledge of the tools you’re using. You don’t want your entire business to depend on software that you don’t understand and that is completely closed. With open source, you always have the option of looking at how the code is written and you are free to adapt the software to your own needs. That is a huge advantage. Even if you never bother to look under the hood, you know that you can do so if you ever need to.

Q How can India play a vital role in expanding the open source world?

I am the first person in my family who went to college. My mother went to school until the age of 16, and my father until the age of 18. I know that there are many countries where going to school until the age of 16 or 18 isn’t common, but in Western terms, it’s unusual. As a child of people without a high-school diploma, I was a nobody and I knew that it wouldn’t be trivial for me to succeed in life.

Access to the Internet and the rise of open source made it possible for me to make the difference. Who I was, where I was born, where I lived — all of that didn’t matter on the Internet. I see that some Asian countries block the Internet. They don’t allow their citizens to have access to resources that could help them to become successful. That’s a recipe for disaster.

When I look at India, I see a huge population of well-educated people. At the Great Indian Developer Summit (GIDS), I saw a large audience of talented developers. Moreover, the percentage of female attendees at GIDS was much higher than in most of the other developer conferences I attended in the rest of the world. All of these observations tell me that India is doing the right things.

As for open source, when I look at the number of visits to the iText site, India is ranked second after the US. When I look at our worldwide revenue, India doesn’t appear in the top 15. In the past, many Indian companies just used iText without ever giving anything in return, often out of ignorance about the open source licence. This is now slowly changing; commercial open source business is growing in India. I can only speak for iText, but now that we see our business growing in India, our trust is also growing and we’re more inclined to invest in India.

India can play a vital role in expanding the open source world by allowing this vast resource of talented people to contribute to open source projects. When you write closed source software, you can’t show the world how talented you are. Open source software is very transparent; everyone can assess the quality of your code. Ultimately, this should improve the quality of code in general.

Q What’s your take on the importance of a community to make an open source solution successful in the market?

Large companies want to use software and do whatever they want with it. They don’t like GPL-style licences because those limit what they can do with the software for free. Usually, such companies are not in the business of selling software. They might be offering software as a service like Google; using a totally different business that relies on software such as Amazon; selling closed source, proprietary products that use open source software internally like Oracle and IBM; or operating their primary business on advertisements, and viewing their users as their product such as Facebook.

Companies like this promote the use of liberal licences such as the Apache Software License. When a developer publishes his source code as Apache software, these companies can use that software without ever having to pay that developer. It’s usually sufficient to sponsor a foundation as long as that foundation succeeds in convincing sufficient developers to create code. This is a great way to make money with open source, but it has some disadvantages. The moment a large corporation decides that the value created by a project doesn’t justify the investment, the ‘charity’ will stop. Oracle dropped GlassFish, IBM backed away from Geronimo, and Pivotal left Groovy.

If this trend continues, an individual, independent open source developer will disappear and open source will only be written by employees in the context of their jobs. Open source code will be distributed by large corporations who can afford to give away their software for free, just as they have gained a monopoly. It doesn’t matter if competitors can also use their software. Their brand is king and whoever wants to challenge them needs a huge marketing budget to make a difference.

The only way to change this evolution for the better is by establishing a community. Just like Blockchain is challenging the omnipotence of banks, the open source community has to return to its grassroots and reclaim the power of the developer.

Q Where do you see open source and iText in the future?

We are currently working on a future for iText that goes beyond PDF. We recently joined forces with Hancom, the South-Korean vendor of productivity software. Hancom is specialised in other document formats (office, epub) and we’re working on products that combine iText technology and Hancom technology.

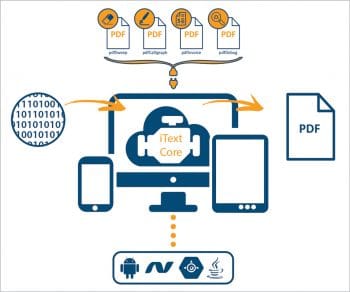

This year, we’ve rewritten iText from scratch and we have released the new set of PDF libraries as iText 7. It is more modular than any of the previous iText versions and it’s also more extensible. We want iText to evolve into a platform on top of which other developers can build their own open source tools and libraries. Once these tools and libraries gain popularity, we want to help these developers to make money with their project. The AGPL is the ideal licence to achieve this; developers can use iText as a library for free in software they distribute for free, under the same licence. As soon as there’s a commercial interest in their software, we will help them with the sales process. We want iText to be a platform developers can use as the foundation for their own development projects, and we want to help them to make money with their project.

We’ll introduce developers to our customers so that they can generate revenue. Our customers will have access to more products and more functionality. If we succeed in setting this up, our platform will grow and everybody will win. This is the future I see for open source and for open source developers.

Q How can Indian developers nurture their career through open source?

Knowing that even MIT is abandoning courses such as ‘The Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs’ in favour of teaching students how to use software written by others, I fear that we’ll see a new form of analphabetism. This is a threat, but also an opportunity; the world will always need talented software engineers who can build libraries.

Indian developers can nurture their career by avoiding this ‘engine-analphabetism’. They shouldn’t be content with merely using open source software. They should learn how open source software works. They should look under the hood of the engines they use and understand how these engines work. Open source allows them to do so as the code is open and should become completely transparent to them. This will give them an advantage over all the developers who use open source libraries as if these were black boxes, because they will understand the humming of their engines. This will benefit the quality of their work and make them more successful as developers.

The Wall Street Journal recently published an article, ‘How the West (and the Rest) got Rich’. The article quotes an American senator, Thomas Massie: “When people ask, ‘Will our children be better off than we are?’ I reply, ‘Yes, but it’s not going to be due to the politicians, but the engineers.’”

Being an engineer myself, I believe this to be true, but there’s more. The major reason why communities became wealthier was the liberation of ordinary people to pursue their dreams of economic betterment. To quote the article: “Liberated people, it turns out, are ingenious. Slaves, serfs, subordinated women and people frozen in a hierarchy of lords or bureaucrats, are not.”

Open source fits perfectly in this philosophy. Open source gives talented developers the freedom to share ingenious ideas with the world and to create wealth in the process— personal wealth as well as wealth for their country and the community, in general.

[…] Programowanie poprzez nieświadome do końca stosowania bibliotek – recently read the article ‘Programming By Poking: Why MIT Stopped Teaching SICP (The Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs)’. It’s the course that taught many software engineers how to write good code. The course has now been abandoned because engineers have changed. Today, developers use libraries without fully understanding what happens under the hood of the library. To quote Professor Sussman: “You grab this library and you poke at it. You write programs that poke it and see what it does. And you say: ‘Can I tweak it to do the thing I want?’” Z <https://www.opensourceforu.com/2016/08/we-are-currently-working-on-future-for-itext-that-goes-beyond-pdf/> […]