This article, which is part of the series on Linux device drivers, demonstrates various interactions with a Linux module.

As Shweta and Pugs gear up for their final semester’s project on Linux drivers, they’re closing in on some final titbits of technical romancing. This mainly includes the various communications with a Linux module (dynamically loadable and unloadable driver) like accessing its variables, calling its functions, and passing parameters to it.

Global variables and functions

One might wonder what the big deal is about accessing a module’s variables and functions from outside it. Just make them global, declare them extern in a header, include the header and access, right? In the general application development paradigm, it’s this simple — but in kernel development, it isn’t despite of recommendations to make everything static, by default there always have been cases where non-static globals may be needed.

A simple example could be a driver spanning multiple files, with function(s) from one file needing to be called in the other. Now, to avoid any kernel name-space collisions even with such cases, every module is embodied in its own namespace. And we know that two modules with the same name cannot be loaded at the same time. Thus, by default, zero collision is achieved. However, this also implies that, by default, nothing from a module can be made really global throughout the kernel, even if we want to. And so, for exactly such scenarios, the <linux/module.h> header defines the

following macros:

EXPORT_SYMBOL(sym)EXPORT_SYMBOL_GPL(sym)EXPORT_SYMBOL_GPL_FUTURE(sym)

Each of these exports the symbol passed as their parameter, additionally putting them in one of the default, _gpl or _gpl_future sections, respectively. Hence, only one of them needs to be used for a particular symbol — though the symbol could be either a variable name or a function name. Here’s the complete code (our_glob_syms.c) to demonstrate this:

#include <linux/module.h>

#include <linux/device.h>

static struct class *cool_cl;

static struct class *get_cool_cl(void)

{

return cool_cl;

}

EXPORT_SYMBOL(cool_cl);

EXPORT_SYMBOL_GPL(get_cool_cl);

static int __init glob_sym_init(void)

{

if (IS_ERR(cool_cl = class_create(THIS_MODULE, "cool")))

/* Creates /sys/class/cool/ */

{

return PTR_ERR(cool_cl);

}

return 0;

}

static void __exit glob_sym_exit(void)

{

/* Removes /sys/class/cool/ */

class_destroy(cool_cl);

}

module_init(glob_sym_init);

module_exit(glob_sym_exit);

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

MODULE_AUTHOR("Anil Kumar Pugalia <email_at_sarika-pugs.com>");

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("Global Symbols exporting Driver");

Each exported symbol also has a corresponding structure placed into (each of) the kernel symbol table (__ksymtab), kernel string table (__kstrtab), and kernel CRC table (__kcrctab) sections, marking it to be globally accessible.

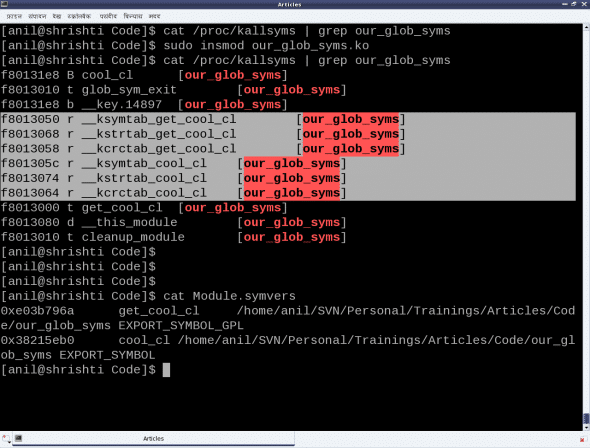

Figure 1 shows a filtered snippet of the /proc/kallsyms kernel window, before and after loading the module our_glob_syms.ko, which has been compiled using the usual driver Makefile.

The following code shows the supporting header file (our_glob_syms.h), to be included by modules using the exported symbols cool_cl and get_cool_cl:

#ifndef OUR_GLOB_SYMS_H #define OUR_GLOB_SYMS_H #ifdef __KERNEL__ #include <linux/device.h> extern struct class *cool_cl; extern struct class *get_cool_cl(void); #endif #endif

Figure 1 also shows the file Module.symvers, generated by compiling the module our_glob_syms. This contains the various details of all the exported symbols in its directory. Apart from including the above header file, modules using the exported symbols should possibly have this file Module.symvers in their build directory.

Note that the <linux/device.h> header in the above examples is being included for the various class-related declarations and definitions, which have already been covered in the earlier discussion on character drivers.

Module parameters

Being aware of passing command-line arguments to an application, it would be natural to ask if something similar can be done with a module — and the answer is, yes, it can. Parameters can be passed to a module while loading it, for instance, when using insmod. Interestingly enough, and in contrast to the command-line arguments to an application, these can be modified even later, through sysfs interactions.

The module parameters are set up using the following macro (defined in <linux/moduleparam.h>, included through <linux/module.h>):

module_param(name, type, perm)

Here, name is the parameter name, type is the type of the parameter, and perm refers to the permissions of the sysfs file corresponding to this parameter. The supported type values are: byte, short, ushort, int, uint, long, ulong, charp (character pointer), bool or invbool (inverted Boolean).

The following module code (module_param.c) demonstrates a module parameter:

#include <linux/module.h>

#include <linux/kernel.h>

static int cfg_value = 3;

module_param(cfg_value, int, 0764);

static int __init mod_par_init(void)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "Loaded with %d\n", cfg_value);

return 0;

}

static void __exit mod_par_exit(void)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "Unloaded cfg value: %d\n", cfg_value);

}

module_init(mod_par_init);

module_exit(mod_par_exit);

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

MODULE_AUTHOR("Anil Kumar Pugalia <email@sarika-pugs.com>");

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("Module Parameter demonstration Driver");

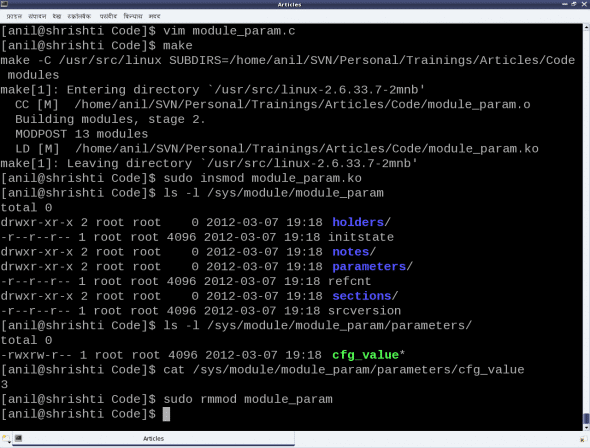

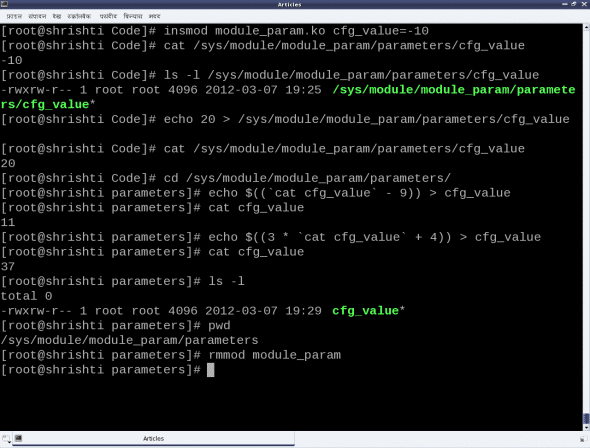

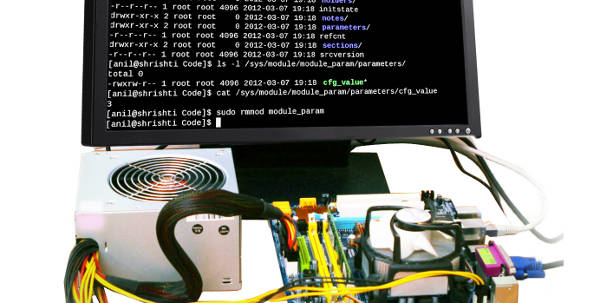

Note that before the parameter setup, a variable of the same name and compatible type needs to be defined. Subsequently, the following steps and experiments are shown in Figures 2 and 3:

- Building the driver (

module_param.kofile) using the usual driverMakefile - Loading the driver using

insmod(with and without parameters) - Various experiments through the corresponding

/sysentries - And finally, unloading the driver using

rmmod.

Note the following:

- Initial value (3) of

cfg_valuebecomes its default value wheninsmodis done without any parameters. - Permission 0764 gives

rwxto the user,rw-to the group, andr--for the others on the filecfg_valueunder the parameters ofmodule_paramunder/sys/module/.

Check for yourself:

- The output of

dmesg/tailon everyinsmodandrmmod, for theprintkoutputs. - Try writing into the

/sys/module/module_param/parameters/cfg_valuefile as a normal (non-root) user.

Summing up

With this, the duo have a fairly good understanding of Linux drivers, and are all set to start working on their final semester project. Any guesses what their project is about? Hint: They have picked up one of the most daunting Linux driver topics. Let us see how they fare with it next month.

hi sir,

I dint undestand the EXPORT_SYMBOL() concept clearly . Its used to access non static global variables . But it can be accesed by source files used for a single module . Then wats its used . Its as good as a static only .

Its use is to make it available for the kernel and other modules, as well.

Hello Anil, the series on Linux device drivers is wonderful pain less way of introducing linux device drivers and makes one who reads them expert on the subject. Thank you very much. are there any more articles expected in this series ??

Yes, there are all together 24 articles in this series of Linux Device Drivers. And they are all out in the print form of the LFY/OSFY magazine till the month of Nov ’12. However, they are a bit lagging on getting them uploaded online.

Surely a great place to start learning about Linux Kernel, Drivers and Modules. Really a great job by Mr. Anil K Pugalia. Your articles are very interesting to read and helped me a lot. And my sincere request to people managing the website, please finish this series and give the appropriate links. :)

Thanks for your appreciation. And I also do hope that they would upload the remaining 7 articles of the series and give the appropriate links.

Thank you a lot for your valuable time and write-ups !!

I am surprised for the post. Blog is awesome for linux geeks.

Anil, I have few dummy doubts, and wish if you could help me out.

Instead of using any embedded boards can we use another PC with the laptop.

I mean to say, we generally prefer boards to connect with our computer for developments (Learning phase).

Instead of the board can I connect another pc/laptop with the current one.

So my Target is a PC(Desktop/Laptop) which is connected to host PC.

Please tell me if I want to know about the each step booting process for target PC.

Thanking you with anticipation.

Yes, it is possible. In fact, serial port on a PC, also acts as a console. So, try connecting that and then booting up. Though, you may have to add some boot arguments.

Hi sir,

Thanks for thses articles. all are awesome.

I have some doubts regarding tty and uart drivers. can u plz write some articles on these.

thanks again for such a great work ur doing for people like us.

Nice device driver book can download from here

http://mir.cr/O509V8VX

This seems to be spam. Please beware.

Hello Mr. Anil,

Thnx for ur clear explanations & efforts. May

I ask you to provide a tutorial demonstrates developing simple CAN,

Bluetooth, or wireless driver …. & how to deal with board’s

registers & use them for sending data, interrupts, receiving data,

etc.

Thanks in advance

Thank you so much for all this tutorials.

Please write some more wifi and USB drivers..

Right now, I am writing on Mathematics in Open Source.

Sir,

how to see what are the scheduling algorithms used in Linux

how to implement new scheduling algorithm in Linux

Hi,

This is a wonderful piece. Learned a lot. Thanks for it!

So I am writing a kernel driver module for a soft processor running Linux.

The driver is for talking to some kind of hardware accelerator.

This accelerator {reads data from/writes data to} a shared RAM, {from/onto} which, the driver must also {read/write}.

The driver also has to talk to this accelerator separately for intimating ready signals on behalf of data on RAM, which works without any problem.

So here is the situation: I want to be able to talk to RAM (/dev/mem) from the “kernel space” part of kernel driver of the accelerator.

Presently, I am using “mmap” form user space to access RAM. What do you suggest I do to achieve this?

Thanks a lot :))

Hello Anil,

I have recently started following your tutorials and they are amazing.I love the way you describe a problem and arrive at a solution. I have a question w.r.t to the above topic. Though I have used EXPORT_SYMBOL(), i get warning during compilation. Let me describe my problem.

myGpio.c happens to be my kernel module, wherein i have a global pointer variable ‘void __iomem *vAddr’ and i do EXPORT_SYMBOL(vAddr).

Some functions of this module is defined in another file myGpio_ioctl.c wherein i want vAddr to be accessible.

I have been using a header file myGpio_ioctl.h where i do ‘extern void __iomem *vAddr’ and this header file is included in both source files. What could I be possibly missing? I did a lot of research for past 24 hrs but i end up at the same solution as described by you, but that that seem to work. Any help would be highly appreciated. Thanks.