Democracy, as a system, is completely dependent on communication, to the extent that when communication breaks down, so does the democratic process. In order for a group of people to participate equally in democracy, they must necessarily share a communication platform, where they can share not just facts, but also views and opinions. Small wonder then, that free speech is prized and cherished by all democracies, and coveted by citizens of almost all countries that are yet to become democracies.

One of the fundamental requirements of free speech and participation in democracy is the availability of a free, open medium and platform of communication that is equally accessible by all members of the democratic community. Almost every culture in the world has a concept of a central community gathering place, where people gather after a day’s work, to talk and share information.

In India, this is typically the village chaupal, in West Kalimantan (erstwhile Borneo), Indonesia, it’s called a ruai. In Afghanistan, it may be called a chaikhana. These community structures have traditionally provided the common platform and free medium for communication.

This type of platform is structured like a circle, and the free medium is air. In a circular structure, everyone has an equal say, because everyone has equal access to the medium and equal reach to every other member of the platform. No special equipment is required to use this medium; ears and a mouth will typically suffice. These structures provided a way for people to voice their opinion, share their concerns and find solutions to conflict through dialogue.

After the industrial revolution and the dawn of the corporation, mass media began to play this role in people’s lives. Newspapers, radio and television became the new media that people used. These media had a much wider reach and they seemed like the perfect democratic tool. However, these media have a structural problem that prevents them from being truly democratic. By virtue of corporate and editorial hierarchy, these media are structured like a triangle (Figure 1).

News, in this model, travels downwards from an elite minority that determines what content is “newsworthy” to the community. The community typically cannot relate the incoming news to their own lives, and either becomes disenfranchised by virtue of lack of representation, or assumes the media version of facts to be true, and that they themselves are an anomaly. At the very least, this influences their participation in democracy, and at worst, they are rendered voiceless in that most fundamental democratic process — debate.

This hierarchical model of modern commercial media requires profits for the media organisation to continue to run. This means that news needs to sell. If a newspaper cannot generate advertising revenue, it will soon shut down. Obviously, with profit as the first imperative, relevance of the content to the community and their feedback must become secondary. Moreover, there is an incentive in preventing communication technology from reaching its true potential. For example, if community radio became fully deregulated, would commercial radio or, for that matter, television, stand a chance?

This skewed set of incentives, and the resulting policies and actions, has led to several communities across the world, particularly in the developing world, becoming alienated and disenfranchised with mainstream society. These communities are particularly susceptible to coercion and this might partly explain the escalating violence in the world today.

This conundrum should be quite familiar to open source enthusiasts, since the basic principles involved are much the same as the ones in the open source vs closed source software debate. To draw a parallel from The Cathedral And The Bazaar, mainstream media follows the cathedral model, while community platforms are more like bazaars. Both paradigms have their value and importance in the structure of society at large. However, in the context of media, the cathedral or top-down model appears to have reached its limits of effectiveness — and, in my opinion, has passed the point of diminishing returns.

The growth of user-generated content on the Internet over the last decade is a clear indicator that as connectivity improves, people are increasingly eager to directly voice their opinions and concerns without the need of mainstream media as an intermediary, particularly since in the real world, no intermediary is perfectly impartial.

The developing world

In the developing world, this uprising of citizen media has been stunted by the uneven distribution of resources, such as infrastructure, connectivity and literacy. While connectivity in the developed world has allowed the blogosphere to become a political force to contend with, most developing countries have an Internet penetration of less than 10 per cent, typically concentrated in urban areas.

Even where connectivity exists, the vast majority of users are only just starting to view the Internet as anything more than email and instant messaging. In many of these countries, even as economies have opened up and globalisation has settled in, entire communities are still disconnected from the rest of the world, primarily because they do not represent a market segment worthy of media representation.

Mainstream media in these countries typically focus on urban issues that relate to economic and political decision makers, rather than the vox populi.

In several of these countries, however, innovation is now taking place to bridge this gap by other means. While Internet penetration remains low, the use of mobile phones is a different story altogether. Most of the developing world has far outpaced the developed world in terms of mobile phone adoption and versatility of usage. Even in places where people earn less than a dollar a day, cell phones are ubiquitous. A medium that uses voice, the oldest mode of communication known to man, amplified by several orders of magnitude, so as to cover unimaginable distances, is as irresistible to a Gond tribal in Chhattisgarh, India, as it is to a street food vendor in Jakarta, Indonesia.

Recognising the potential of this medium, several groups are now actively engaged in developing technology to allow people to use their voice to connect themselves and their communities to the rest of the world. One of the first tools of this new age of innovation is the audio portal.

An audio portal?

An audio portal (Figure 2) is essentially a website with a lot of audio content that can be accessed both through the Web as well as by phone.

While the Web interface is usually like a blog, the phone interface is an IVR (Interactive Voice Response) system, where users press keys to navigate through menus and content. In more advanced IVR systems, voice recognition may be used, though this is still limited to the well-documented accents of the English language. The Web interface is very similar to a blog, and several audio portals do use the blog layout.

Behind the scenes, the platform will also provide an interface to manage posts. Early implementations of audio portals tended to rely on specialised moderation consoles, which have media-previewing capabilities as well as functionality for moderators to add metadata, such as a summary and title, to the content to make it friendlier to users on the Web.

Users will typically call the IVR interface to record and listen to content using their cell phones, while Web users will access the website interface to listen to the audio posts using a browser, and leave comments in text, which then may or may not be converted to audio using a text-to-speech system.

People who own the latest Android or iPhone may find the idea of an IVR interface to browse content somewhat counter-intuitive, since it makes no sense to call in and scroll through a set of menus, particularly with an irritatingly monotonic voice rattling out instructions all the time, when you can simply open the Web page on your cell phone’s browser, and read.

The graph in Figure 3 may help clarify why a purely visual interface is not adequate to reach the majority of the world.

The percentage of Internet users, even among the mobile phone users of the world, is a fraction of the percentage of people using their phones purely for voice and SMS. While mobile Internet use is, and will continue to be, on the rise, the bulk of the world will continue to be on voice for some time to come.

This is also historically consistent, since most societies have far stronger oral traditions than written ones. Voice captures much more than simply language. Tone, quality, emotion are all interwoven in the spoken word. If a picture is worth a thousand written words, then a spoken word counts for at least a few hundred… not to mention that drawing an attractive picture takes considerably more skill than speaking!

What makes mobile phones particularly attractive as a medium, though, is the two-way nature of the medium. With radio and television, though the reach may be much wider than mobile phones, the ability to respond immediately to what you hear or see — on the same platform, at the same level as the source, which is extremely valuable in fostering dialogue — is missing.

The audio portal concept caters to every cell phone, whether mass-market or smartphone equally, which works very well to level the platform. Most importantly, audio portals use technology, skills and other resources that are available now, as opposed to those that require extensive “capacity building” exercises. This is probably the reason why audio portals, as a tool, find more favour with grassroots workers and members of the community, rather than with technology evangelists and academia.

The technology

Audio portals utilise relatively simple technology, most of which has been around in the open source world for some time. An audio portal will typically consist of a phone interface (either fixed-line or mobile), connected to a content-management system (usually a database) and a Web front-end, via an IVR running on a soft switch or software PBX system. Two examples of audio portal platforms are Swara and FreedomFone.

Swara

Swara is an open source project, originally written as a research project by students and professors at MIT to augment the outreach and activities of CGNet, a people’s discussion group working with indigenous communities in central India. CGNet was started by veteran journalist Shubhranshu Choudhary, who returned to Central India, where he grew up, to find it torn by violence. Probing to find the reason for the conflict, he quickly realised that open, accessible community media would be a key component of any solution to the conflict. Given that Internet penetration in the region is less than 1 per cent, and community radio is limited by regulation, the next best medium for a community platform was the mobile phone.

The first pilot of Swara was deployed in Bengaluru for use by indigenous communities in Chhattisgarh and neighbouring states in February 2010. Today, the pilot receives over 300 calls a day, and the team is working on building the platform out as an open source project for deployment in other locations. The first replica of the project went live in Indonesia in December 2011.

Swara uses a combination of the Asterisk PBX system in combination with the LoudBlog audio blogging platform, with the integration written in Python. The tested interfaces are GSM gateways (Topex Mobilink, etc) and fixed lines (PRI/BRI) using a Digium telephony card.

FreedomFone

FreedomFone was developed by Alberto Escudero Pascual and Louise Berthilson of IT46, a Swedish IT consultancy, for the Kubatana Trust in Zimbabwe. It was created for many of the same reasons as Swara was developed in India, i.e., lack of impartial and open commercial media, and the need for local and community-level reporting. The FreedomFone pilot, a weekly audio magazine called Inzwa, has been running in Zimbabwe since July 2009, and received over 2,500 calls between July and September 2009. FreedomFone’s team is also working on developing the platform as a user-friendly DIY IVR kit, and is keen on replicating the model in other areas.

FreedomFone uses the FreeSWITCH soft switch to interface with telephony devices such as the Mobigater and Office Router GSM gateways. The content management system is written in CakePHP, and FreedomFone additionally uses the Cepstral speech synthesis system for text-to-speech conversions. The stated objective is to create a purely phone-accessible platform.

Deployment 101

Both platforms have an almost identical design, as would most audio portal software. This is almost analogous to how traditional websites are built, with the choice of platform being similar to the choice between different Web frameworks. Just as you will find lots of different opinions and preferences for Web platforms among Web designers, you will find that the few implementers of audio portals are just as varied in their preferences for platforms. This usually depends on which platform the implementer is most familiar with — and if you are implementing your own, one is essentially as good as the other.

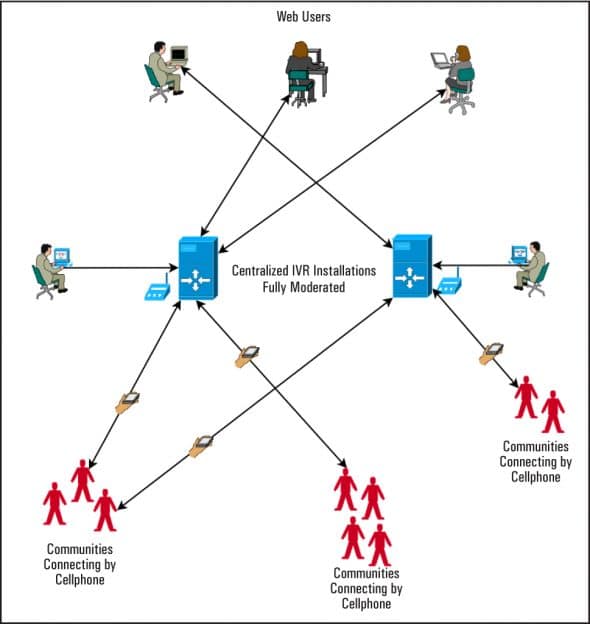

The key question, irrespective of which platform you use, is one of deployment strategy. At present, most implementations of audio portals as community media platforms are centralised instances deployed by a single organisation or group, with a specific agenda (such as news, healthcare or governance).

Centralised function-oriented deployment

Centralised, function-oriented deployments require content of a certain quality and, as a result, must usually be moderated. Speech-recognition technology, particularly in the area of automatic transcription, is still a far cry from being very accurate. As a result, moderating a function-specific audio portal is still a manual job, for the most part.

Typically, audio portal moderators will need to listen to each message and summarise and/or transcribe it. Beyond transcription, there may be more work to do to improve the quality of the content for the specific purpose of the deployment, like sound quality clean-ups and edits, fact verification (if journalism is the function, for example) and categorisation. All of this work is further exacerbated in a centralised deployment, since all incoming calls come to the same central hub (see Figure 4).

In India, and other countries where long-distance call charges are higher than local call charges, centralised platforms also suffer from an added cost element, since all callers must call the central number, regardless of their own locations.

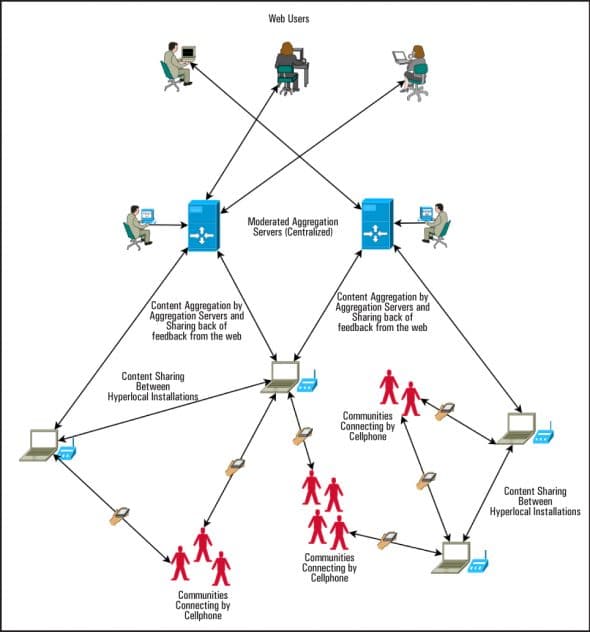

Hyperlocal deployments

An alternative model is a hyperlocal community-oriented one. In this model, an instance of the platform is deployed at the community level and maintained by community members. Such community-level audio portals could be used as voice-based bulletin boards. By managing the size of the user base, and ensuring a manageable user adoption rate by limiting publicity to word of mouth, communities could eliminate the need for moderation by making sure everyone on the platform was known by the others and therefore accountable to the community.

Several communities can then choose to link their platforms, either by sharing content, or by simply listening to each other. This will eventually lead to an organically expanding network, where people can choose which deployments they want to subscribe to, much in the same way as Internet users subscribe to different forums and websites. This would also ease the burden on centralised deployments already in existence, since they could then simply trawl the community bulletin boards for usable content, rather than filter out unusable content on their own incoming stream. As you can see from Figure 5, the hyperlocal model offers more avenues for collaboration and the cross-fertilisation of ideas between communities than the centralised model.

A word of caution: This approach is still experimental, and needs several more deployments before it can be considered a best practice. However, for communities interested in improving their information access and level of participation in mainstream society, this is a very worthwhile experiment to take on. Both systems described here can be installed on a mid-range notebook computer.

The software is all open source and free for non-commercial use. Mobile interfaces like GSM gateways and mobile ATAs are relatively cheap — a Matrix SETU ATA 211G would cost roughly US$ 120, and the Mobigater is priced at about US$ 50. The total cost of setting up a local IVR installation and running it through a year, including the cost of connectivity, is typically less than US$ 200 a year.

Of course, the most important thing to remember while setting up an alternative communication platform is that while technology will certainly provide the tools, the key to success is to build a strong community around your platform, and quickly demonstrate value to the community from participating. This is where most of the hard work lies.

It would be interesting to see how well the open source community in India takes to these projects and how quickly the hyperlocal model can be tested with several more installations.

[…] Human beings are the only species on earth with the ability to communicate complex ideas through language. Speaking and listening have been the basis of human society since people started living in communities. In fact, the words “community” and “communication” share a common etymology. Read more… […]

how can i get more ideas & more explanation on this topic….please provide me some resourses & sites

Great post explaining audio portals. Thanks!