From operating system commands to menu entries, almost every new computing term is in the English language. The age-old problem for translators is to convey the collocations, and moods—baggage that doesn’t often translate too well. Software translators, therefore, must be particularly careful in dealing with such terms, for fear of producing awkward and stilted work, which could mar the FOSS experience. This is the paradigm within which we’ll critique the Indian-language FOSS desktop and gauge its state of readiness for you, the user.

Naturally, I can only comment on the languages that I know, and I pick Hindi for this review. I installed support for the language in my Ubuntu 8.10 GNOME desktop. Kaisa tha, then?

Installing and activating local-language menus

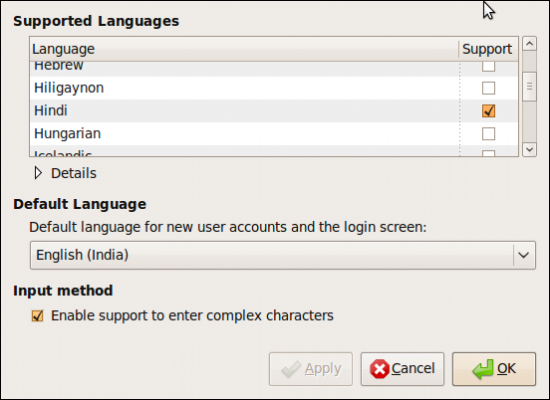

Very few distributions have Indian language menus installed by default. In Ubuntu 8.10, install the feature yourself, as follows: System menu→Administration→Language Support (Figure 1). Now, in the window that appears, select your language, and Ubuntu will download the fonts and menu files. It’s a large download! Make sure you have a fast Internet connection. This step will also install your language keymap, so that you can word-process in your language. So if you can type in your language as the earlier article in this series described, then you’ve already got translated menus installed. Neat, huh?

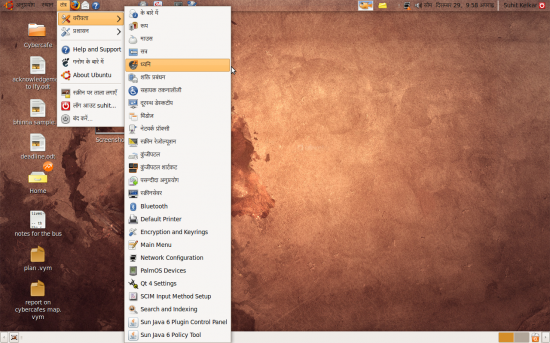

But you’ll have to activate the menus. Log out. Now, in the login window, select the Options menu and then Language. Choose your language here. Log in again with your user name and password. Hey presto, aapke menus ab Hindi mein bhi! (Refer to Figure2.) Kya khoob baat hai…

Khidki or window?

…or is it something else? Most of the common e-terms such as open, save, view, edit and rename are translated competently. One place where the translators have excelled in particular is ‘Raddi mein bheje’ (of course, it’s written in Devanagari script in the menus!) which is a delightful and comprehensible translation of ‘Send to Trash’. It translates the concept of a trash can into that of a pile of raddi on the image level. Way to go! Immigrant concept, naturalised fully.

But a very few words, though not quite lost at the airport, are delayed by the customs. Consider ‘page layout’, and then ponder over the Hindi translation in the OpenOffice.org suite of Ubuntu 8.10—prushtha vikhandan purvavalokan. I’m no Hindi expert, and presumably more people than Ashutosh Rana speak like that—no offence intended—but everyone doesn’t. And I have never adhisthapit (install) any vancchit (default) applications. These concepts had better be trans-created instead of translated. They look really awkward in the guest language.

These are rare, very rare (and comic) issues with the Hindi desktop. The translators are not entirely to blame. What can they do, when for example, there is no adequately co-locational term for ‘window’ in Hindi? The word ‘khidki’ cannot be suggested except in humour, until the word accumulates new meaning. Dear, dear me. A bold alternative could be to translate the concept of a ‘window’ using an Indian visual (as was done while translating the ‘Trash Can’ concept). ‘Jharokha’ here could be a choice. It has co-locational pedigree as well as a really nice sound.

The desktop menus, right-click menus, dialogue boxes and mouse-over info have been translated, as well as the menus of the popular applications such as OpenOffice.org writer, spreadsheet, presentation, Evolution mail, dictionary, movie player, Pidgin instant messenger, Gedit, Terminal, and GNOME games. Mozilla Firefox is not touched. As for the Rhythmbox music player, it is only partially translated. Information and warning messages are also translated. And files can be renamed in your language script also. Rather bafflingly, the help files have not been translated at all!

At its current state, the desktop in our test distribution looks as if a native speaker would be at home with it. Oh, how he can vikhanditise his prushts…

Translate your own desktop

Eleven Indian languages are being worked into KDE4; GNOME has 15. There’s lots of work still to be done. For example, the FOSS Hindi desktop in GNOME 2.24 is 80 per cent translated. The KDE4 desktop is 70 per cent translated, according to their websites. And maybe there are translation issues in a couple of places. For example, very ‘propah’ Sanskritised Hindi is used, but that is not the only Hindi spoken in India. There’s scope for translators who want to see ‘their’ language represented on the desktop. That must be the case for many Indian languages.

So, how do you get involved? You link up with other volunteers, that’s how. Visit the KDE and GNOME websites; they have separate sections for localisation. Or you can visit your distribution’s website and join their team. For Ubuntu, visit the Ubuntu-India website. For Fedora, your place is translate.fedoraproject.org. And so on, for your distribution.

Generally, the process of localisation is this: the material to be translated is uploaded on these or related websites, and you have to translate it in a special editor. That done, you submit your work by e-mail or upload. Simple! Not at all time-consuming either. It’s a great way for non-techies to contribute to FOSS, isn’t it?

Sign-off

Localisation is associated with a fair bit of hype; but the FOSS localisation communities, especially the Indian ones, if Hindi is any indication, are actually implementing it in a usable way.